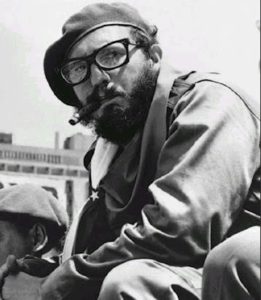

History may yet absolve Fidel Castro (1926-2016) just as he predicted while representing himself at trial for the 1953 failed coup attempt on Cuban President Fulgencio Batista (1901-1973). President Barack Obama used the 2014 Christmas season to announce his intention to relax tensions and work toward normalizing relations with the Castro government entering its 56th year.

History may yet absolve Fidel Castro (1926-2016) just as he predicted while representing himself at trial for the 1953 failed coup attempt on Cuban President Fulgencio Batista (1901-1973). President Barack Obama used the 2014 Christmas season to announce his intention to relax tensions and work toward normalizing relations with the Castro government entering its 56th year.

Two years later, some details are still being negotiated between the two countries. It has been clear, however, that talks regarding normalization have been underway since at least 2012. It was a given that travel restrictions on Americans wishing to visit Cuba would be lifted and restrictions that drape some exchanges (i.e. cultural and educational) in red tape would be less onerous.

Whether the 1961 trade embargo – la barrera mas grande – will be lifted is the decision of a Congress entering into the heart of an election season. It is a Congress controlled in both houses by a Republican party with a history steeped in political pandering to anti-Castro Floridians. However, it is a step in the right direction that in May 2015 the U.S. State Department rescinded Cuba’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism.

The Obama decision to support the lifting of the embargo will not be rubber stamped. There will at least be an appearance of debate, one final nod to the last, aging bastion of rebels both literal and ideological that populate a politically vital south Florida that still harbors lingering feelings of the disaster at the Bay of Pigs in 1961.

The United Nations General Assembly held an annual vote on the “necessity of ending the economic, commercial, and financial embargo imposed by the United States of America against Cuba.” Between 1992 and 2012, only two member nations voted “no” each year: the United States and Israel. The “yes” votes rose yearly to 188 in 2012. The “no” votes reached a ceiling of four in 1993 and then again in 2004, when the U.S. and Israel convinced the Marshall Islands and Palau to join the rigid stance against Cuba.

The last of the Cold Warriors may be disappointed with the lack of ferocity in the modern GOP’s fight against Cuban communism. The party has severed its long marriage to rabidly reflexive anti-communism in favor of a more beautiful and profitable, multinational lover. The potential of opening a new Cuban market – 90 miles from the American coastline – to the largest American corporations has the Corporatists from both parties salivating for dollars. The CEO’s of Big Agriculture (i.e. Monsanto, ADM, Dow), Big Finance (i.e. Chase), and Big Construction (i.e. Halliburton) will be the Meriweather Lewis & William Clark of an American Latin America. Globalists behind the IMF and the World Bank will not lag far behind.

It was this corporatism, the U.S. version of economic colonization, which led to the embargo originally. By 1959, U.S. corporations had owned or controlled more than three-quarters of Cuban land, 90 percent of its public services, and 40 percent of its sugar industry, Cuba’s chief export crop. Cubans lost their ability to remain self-reliant when the Batista regime literally sold the air, land, and water from around them.

Castro saw his country crippled by a Batista administration corrupted by the endless stream of financing that flowed south from the U.S. into the coffers of Batista loyalists. Much of the financial steam jolting Havana into global recognition flowed through the nameless, faceless accounts of American organized crime bosses.

The country freed by the passions of General Maximo Gomez y Baez and Jose Marti, Fidel’s hero, was now a haven not only for Coca-Cola and Chevrolet, but also for the socially corrupting influences of the Italian-American and Jewish-American mafia. Mobsters like Meyer Lansky were thinking Latino Las Vegas as Fidel, brother Raul, and Che Guevara were trying to prevent a Latino Bangkok from ruining the distinctly Cuban culture that had formed in the years following independence.

What happened after the Castro ascension has become the history told by American textbooks for decades: the surprising unveiling of communist leanings evilly thrust upon the Cuban people by Castro after taking dictatorial power; the shocking defeat of the anti-Castro, CIA-funded, Cuban exile freedom fighters at the Bay of Pigs; the unholy alliance between Castro and Russia premiere Nikita Khrushchev that led to missiles in Cuba and a world on the brink of nuclear destruction; potential Castro involvement in the Kennedy assassination; and a Castro that would not die despite the best wishes of every right-thinking Cuban who hoped, wished, and prayed for true freedom for their fellow countryman.

If the perspective placed on these events in American schools had been true, Cubans would be a people needing saving, a country worth opening to the goodness of a Pax Americana.

While Cubans should be excited at the prospect of having a freer relationship with its largest neighbor and a more active role with the American citizenry, it should be leery of other potential effects:

- Will there be international pressure for Cuba to take predatory loans from the IMF/World Bank?

- Will there be an eventual demand for Cuba to join NATO, thus binding them to mutual defense pacts with countries such as Luxembourg and Latvia, agreements that erode their previously held national sovereignty?

- Will the United Nations and the IAFA begin demanding access to defense sites as a way of maintaining “goodwill” in the hemisphere?

- Will Cuba have to globalize its economy to meet international demands to do its part environmentally?

- Will Cuba be forced, as part of a new, freer regional trade pact with the NAFTA powers, to engage in unwanted corporate partnerships masked as sponsorships and charity?

- Will Cubans be entranced by the almost immediate rise in pay? And will this temporary economic euphoria blind them from the longer-term effects on costs?

Cubans have more to consider than the hope of having a Major League Baseball team in Havana, selling cigars to Chicago businesses, and attracting tourism bucks from Bostonians. Their future and their past are at stake. The next generation will decide the future of its own Cubanity.