For thirty years, Iraq believed that the small oil-rich nation of Kuwait was its own. In 1961 and 1973 Iraq had tried to legally and militarily take over Kuwait. The border dispute between the two had transitioned through hot and cold spells dependent, it appeared, upon Iraq’s financial stability. Though the relationship was amiable enough for the United States to use Kuwait as a third-party conduit for secret arms transfers to Iraq in the 1980’s, by 1990 Saddam Hussein (1937-2006), the fifth president of Iraq, was feeling the financial strain of his decade-long war with Islamic fundamentalists in Iran.

For thirty years, Iraq believed that the small oil-rich nation of Kuwait was its own. In 1961 and 1973 Iraq had tried to legally and militarily take over Kuwait. The border dispute between the two had transitioned through hot and cold spells dependent, it appeared, upon Iraq’s financial stability. Though the relationship was amiable enough for the United States to use Kuwait as a third-party conduit for secret arms transfers to Iraq in the 1980’s, by 1990 Saddam Hussein (1937-2006), the fifth president of Iraq, was feeling the financial strain of his decade-long war with Islamic fundamentalists in Iran.

Hussein decided it was time to stake his claim in Kuwait by force. On August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait. By mid-August, Hussein had amassed 200,000 troops within or near the Kuwaiti border in southern Iraq.

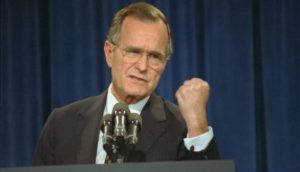

On August 5th, President George Herbert Walker Bush (“41”) emphatically stated, “This will not stand.” War was already on the mind and lips of the American president, the successor to Ronald Reagan, well before it entered the hearts and minds of the American people.

Three objectives would be met before the United States could act militarily:

- Secretary of State James Baker had to assemble a global coalition to serve as the Kuwaiti defense force, which he quickly succeeded in doing.

- The Saudis royals – the House of Saud – would have to allow the U.S.-led coalition to use Saudi soil as a base from which to operate – which they did, despite vocal and influential opposition from Islamic extremists within Saudi Arabia.

- The hearts and minds of the American people must support the military invasion of Iraq in defense of Kuwait.

The third objective, some Bush administration officials believed, would be the biggest challenge.

House of Bush, House of Saud author Craig Unger summarized the public relations problem faced by Bush officials. “If atrocities against the Kurds didn’t stir the U.S. populace,” Unger wrote, “why should the invasion of Kuwait, a border war of sorts?” It was a good question to ask about an American society still both leery and weary of “another Vietnam.”

If politicians were to make the case alone, it was going to be a tough one to make. They certainly could not argue that the U.S. should defend democracy. Only 65,000 of two million Kuwaitis could vote. A Kuwaiti voter had to be a male who could prove ancestry dating back to 1920. Kuwaiti women had no voting rights. Executive power was held exclusively by the emir who was chosen by a member of Kuwait’s ruling al-Sabah family. Democracy was non-existent in Kuwait. How could it be defended?

Could it be argued that Kuwait was a popular ally of the most prominent U.S. politicians? Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-NY) had once described Kuwait as “a poisonous enemy of the United States” famous for its “singularly, nasty” anti-Semitism.

Hearts & Minds, Hearts & Minds… Hill & Knowlton

If the Bush administration could make a convincing case for the oil argument (more oil leads to higher supply, which would equal lower gas prices), then maybe an America still reeling from a recession could be convinced to invade Iraq. After all, if Iraq controlled Kuwait and then moved into Saudi Arabia, Hussein would then control over 40 percent of the world’s oil production. President Bush personally and publicly nixed this argument, however, when he told the country that “the fight isn’t about oil.” Most polls also showed that the American people didn’t believe oil was a valid reason to get involved.

How could Americans be convinced? An $11.9 million public relations campaign funded by the Kuwaiti government was a good place to begin. Kuwait’s royal al-Sabah family (the Kuwaiti government) invested millions into twenty public relations agencies, lobbying groups, and law firms within the United States.

By August 11, 1990, Kuwait had hired Hill & Knowlton, the world’s largest PR firm and the one with incalculable ties to influential D.C. politicians. The Kuwaiti government operated in the United States under a vague title – Citizens for a Free Kuwait, the implication being that the group was compromised of American citizens, which is was not. It was a front group for Kuwaiti activities that were funneled through Hill & Knowlton.

Hill & Knowlton was a bipartisan PR firm. Its chairman, Robert Gray, had been a key aide in the Reagan administration, while its vice-chairman, Frank Mankiewicz, had worked for both George McGovern (who lost to Richard Nixon in 1972) and Robert Kennedy. Craig Fuller, the former chief of staff to then Vice President George H.W. Bush, ran Hill & Knowlton’s local – and most powerful – office in Washington D.C.

Hill & Knowlton used 119 executives on the Kuwaiti account, all strewn across the United States and all responsible for a region of the country. Its one and only goal was to make the American public believe that it wanted and needed to protect Kuwait against Iraq and Saddam Hussein. In a bit of word association politics, President Bush began mispronouncing Hussein’s first name, calling him Sodom instead of Saddam and thus recalling the twin cities of evil in the Bible.

Hill & Knowlton’s first attempt at turning the popular tide was to organize a Kuwait Information Day on twenty of America’s most influential college campuses. On September 23, 1990, Hill & Knowlton used its links to America’s growing evangelical mega-churches to organize a National Day of Prayer for the Kuwaiti people. The firm’s bipartisan executive board led to successes with both the liberal academic left and the conservative evangelical right.

On September 24, 1990, America celebrated Free Kuwait Day. Grass roots rallies, funded by the not-so-rootsy PR giant, were held in the country’s largest media markets. Tens of thousands of bumper stickers, t-shirts, and propagandistic media kits on Kuwaiti history were distributed to media outlets in the included markets.

Hill & Knowlton’s Lew Allison, a former news producer for CBS and NBC, created two dozen video news spots for the various evening news programs. To be clear, reporters from the respective stations did not create the spots to be shown on their newscasts. A former network news producer working with a PR firm being paid by the Kuwaiti royal family created the spots. There were no disclaimers. They ran as regular news segments. This was not the first time this practice had been implemented, nor would it be the last. Why should we assume that this does not happen today or tonight on the evening news?

Nayirah and The Baby Killer

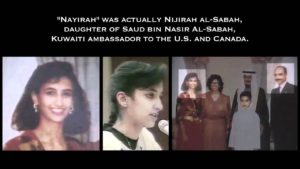

The next PR move was the most powerful of the overall al-Sabah-funded campaign. On October 10, 1990, Hill & Knowlton presented its evidence before the congressional Human Rights Caucus. The chief witness was a 15-year-old Kuwaiti girl with emotionally wrenching eyewitness accounts of Iraqi atrocities. The teary-eyed girl went by her first name, Nayirah, to protect her family, still in Kuwait, from persecution. This courageous Kuwaiti teenager cried as she testified about her stint as a volunteer at the al-Addan hospital. Iraqi soldiers had come into her hospital and had made their way to the pediatric wing. Once there, they took babies out of incubators and inhumanely left them “on the cold floor to die.”

The next PR move was the most powerful of the overall al-Sabah-funded campaign. On October 10, 1990, Hill & Knowlton presented its evidence before the congressional Human Rights Caucus. The chief witness was a 15-year-old Kuwaiti girl with emotionally wrenching eyewitness accounts of Iraqi atrocities. The teary-eyed girl went by her first name, Nayirah, to protect her family, still in Kuwait, from persecution. This courageous Kuwaiti teenager cried as she testified about her stint as a volunteer at the al-Addan hospital. Iraqi soldiers had come into her hospital and had made their way to the pediatric wing. Once there, they took babies out of incubators and inhumanely left them “on the cold floor to die.”

Rep. Tom Lantos (D-CA), horrified, commented, “We have never had the degree of ghoulish and nightmarish horror stories coming from the totally credible witnesses that we have at this time.”

President Bush referred to the incubator story on at least five documented occasions over the next five weeks. He said he was happy to have the atrocities highlighted on CNN, who gladly highlighted them. And he was. The media had all but ignored global reports of Saddam’s atrocities against the Kurds and his opponents throughout the 1980’s when he was at war with Iran, then an enemy of the United States after the hostage crisis. Now it was 1990 and the media suddenly and curiously cared about his atrocities in Kuwait.

Amnesty International, no fans of the Bush administration, qualified the story, estimating the number to have been over 300 babies. The Nayirah story – with Amnesty International estimates – became a global story repeated by everyone from the New York Times to the Sunday Times of London to CBS, CNN, and Time magazine.

President Bush, in large part because of the Nayirah story, could now compare Saddam to Hitler, another word association tactic often used as a link to evil. “I don’t believe that Adolf Hitler ever participated in anything of that nature,” Bush said. The implied message of the administration in the following weeks was that Europe waited too long to stop Hitler before he ravaged Europe, so how can we allow Saddam to do much worse? Immediacy was stressed on countless occasions.

Supporters of U.S. involvement began commonly using the phrase “baby killer” to describe Hussein. And, after all, what compassionate American wouldn’t want to do all he or she could do to stop a “baby killer”? The association of demonized figures to the potential harming of children is a successful strategy often used by those wanting to move the emotional pendulum of American sympathy toward a cause – gun control, tracking devices, vaccinations, pharmaceuticals, and yes, even war.

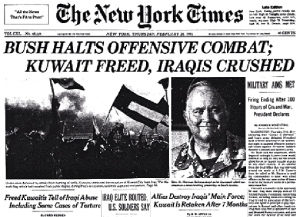

And so, America did just what their emotional strings were tugged to do – support the effort to chase the “baby killer,” who was also now the media-friendly “Butcher of Baghdad.” On January 16, 1991, the air offensive of Operation Desert Storm began, and there was war in the Gulf. The American effort was propped up by a fervent populace fully supportive of its president. Yellow ribbons were wrapped around trees in Middle America and flag poles hung from every white-picketed lawn from sea to shiny sea.

On February 28, 1991, President Bush announced a cease-fire; Kuwait had been liberated. Frankly, so had the president’s approval rating, which hovered between 80 and 90 percent in the immediate weeks following the war. The baby killer of al-Addan hospital had been stopped and the children of Kuwait were safe.

Nayirah’s story had been the turning point of public opinion toward the defense of Kuwait. It was dramatic. It was moving. It was powerful.

One organization, Middle East Watch, a New York-based human rights organization, also believed it was dramatic, moving, and powerful. They just didn’t believe it was true. Middle East Watch decided to do something Time, CNN, CBS, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal didn’t – they decided to actually investigate the story rather than just repeat the story.

Middle East Watch sent investigator Aziz Abu-Hamad to Kuwaiti hospitals. Abu-Hamad interviewed doctors who uniformly refuted the incubator stories. In a January 6, 1991 memo, Abu-Hamad reported his results. He could not find a single family whose baby had been left to die on any cold floor after being taken from an incubator. He also investigated a story that had circulated through some U.S. media outlets regarding the kidnapping, torture, and killing of some prominent Kuwaiti citizens. Abu-Hamad found those prominent citizens alive and well in Kuwait – not kidnapped, not tortured, and not dead.

Dr. Mohammed Matar, the director of Kuwait’s primary health care system, and his wife Dr. Fayeza Youssef, chief of obstetrics, later reported that Iraqis did not take any babies from hospitals. “I think this is something just for propaganda,” Matar said about the incubator story.

Amnesty International decided to investigate their numbers. Amnesty’s conclusion produced a retraction of their earlier estimate of 300 dead babies. Now, upon investigation, they “found no reliable evidence that Iraqi forces had caused the deaths of babies by removing them from incubators.”

How did this happen? Who was Nayirah and from where or whom did this story emanate?

Nayirah, as it turned out, was the daughter of Saud Nasir al-Sabah, the Kuwaiti Ambassador to the United States. The royal and ruling family of Kuwait, the al-Sabah family, had paid for Hill & Knowlton’s services. Hill & Knowlton had used Nayirah to tell a fictional story that would produce a desired result. And it did. Dramatic. Moving. Powerful. FICTIONAL. Successful. Who in the White House knew Hill & Knowlton’s strategy? How high in the chain of command was its approval?

Nayirah, as it turned out, was the daughter of Saud Nasir al-Sabah, the Kuwaiti Ambassador to the United States. The royal and ruling family of Kuwait, the al-Sabah family, had paid for Hill & Knowlton’s services. Hill & Knowlton had used Nayirah to tell a fictional story that would produce a desired result. And it did. Dramatic. Moving. Powerful. FICTIONAL. Successful. Who in the White House knew Hill & Knowlton’s strategy? How high in the chain of command was its approval?

Bush, Inc.: A Preface to War in the Gulf

There are, however, a few things that can be stated for certain. This was not the first nor was it the last contact the Bush family and its peers would have with the ruling al-Sabah family of Kuwait.

The al-Sabah family – thirty years earlier – had granted oil concessions to George H.W. Bush’s Zapata Oil Offshore company. Zapata was given the contract to build Kuwait’s first offshore oil well. It was Zapata’s first oil well project outside of the United States. For granting the rights to Zapata, Bush was forever grateful to the al-Sabah family.

In the reorganizational aftermath of the first Gulf War, the Carlyle Group, a private equity firm based in Washington D.C., began receiving massively profitable concessions for its businesses in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Carlyle’s company, BDM, a military construction firm, won contracts for technical support services for the Royal Saudi Air Force as well as computer systems design and construction in Kuwait.

In 1993, James Baker, Bush’s former Secretary of State during Kuwait’s supposed liberation, traveled to Kuwait with former President Bush and his two sons, Marvin and Neil Bush. Baker represented Enron, the Houston oil and energy company, in their bidding to rebuild a Kuwaiti power plant. Marvin Bush represented a company selling electronic fences. Neil Bush was selling antipollution equipment to Kuwaiti oil contractors. All three secured contracts. President Bush played to packed rooms in the role of “Liberator.”

Baker had joined the Carlyle Group in 1993. Bush joined in 1995 as a Senior Advisor. Carlyle’s companies reached the position of being the most successful foreign companies in Kuwait.

Not everyone chose to profit from the war. General Norman Schwarzkopf refused to represent business interests in Kuwait after his retirement from the military. The media hero of the Gulf War did not want to be seen as a profiteer. “I told them no,” the General said. “American men and women were willing to die in Kuwait. Why should I profit from their sacrifice?”

Aftermath: Kuwait into Syria

America should not be propagandized into a war. It was not the first occurrence of propaganda turning the populace toward supporting military action. But what does it say about freedom of the press and the fourth estate when public relations firms control news pieces? What does it mean when presidential decisions lead to personal profits?

The movie played out on CNN as “our first televised war.” Schwartzkopf was the heroic protagonist. Hussein was the antagonist. Arthur Kent played the role of “Scud Stud” as beautiful billion-dollar bombs zig-zagged across the desert sky at night. Voices that Care produced a hit song with the same name. And we were all John Rambo once again asking “Can we win this time?” Billions of dollars later, with thousands of Iraqis dead in their then-unstable country, all that remained was death and greed.

The movie played out on CNN as “our first televised war.” Schwartzkopf was the heroic protagonist. Hussein was the antagonist. Arthur Kent played the role of “Scud Stud” as beautiful billion-dollar bombs zig-zagged across the desert sky at night. Voices that Care produced a hit song with the same name. And we were all John Rambo once again asking “Can we win this time?” Billions of dollars later, with thousands of Iraqis dead in their then-unstable country, all that remained was death and greed.

The blanket of blame descends onto both sides of the faux political aisle. The Gulf War was not a war of liberation, it was not a war of freedom. It was not a war where its soldiers can claim some sort of idealistic protection of American liberty. It was not a war to make the Middle East safe for democracy. It was a war to make Kuwait safe for American corporatism. It was a war where the media, the congress, and the American people yellow-ribboned the military-industrial complex into a dominant business entity in an oil-rich nation.

One day we may understand what we have done and continue to do. But today, as images of bloody Syrian children and refugees begging for homes blast through our 70-inch televisions and stereo surround sound in a Fahrenheit 451 sort of media-as-life world, war continues to expand and Americans continue to get sucked in – the political right by the thought of destroying a supposed sadistic dictator and the political left by allowing the media to convince them that they are helping the women and children of Syria.

And you want Russia next? Or North Korea? Iran?