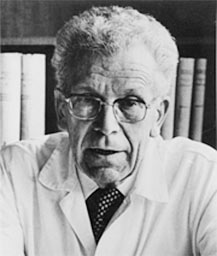

Hans Asperger (1906-1980) is the professor of child psychology who coined the term Autistische Psychopathen (autistic psychopathy), or Autismus. He is said to be the discoverer of what we now know as Autism, and he was the first to make a public speech on the subject, doing so in 1938 amidst the rise of German Nazi Party influence across Europe. While some view Asperger as one of the central figures of the 20th century, others view him as a Nazi sympathizer eventually concerned only with self-preservation.

Hans Asperger (1906-1980) is the professor of child psychology who coined the term Autistische Psychopathen (autistic psychopathy), or Autismus. He is said to be the discoverer of what we now know as Autism, and he was the first to make a public speech on the subject, doing so in 1938 amidst the rise of German Nazi Party influence across Europe. While some view Asperger as one of the central figures of the 20th century, others view him as a Nazi sympathizer eventually concerned only with self-preservation.

What Asperger discovered was not that for which he is usually credited – Asperger’s Syndrome. What Asperger and his colleagues at the University of Vienna in the 1930s really discovered was now what we call the “Autism spectrum,” which Asperger and colleagues called the “Autism continuum.” It was the discovery that Autism was a life-long condition that embraced a wide variety of clinical presentations. Asperger saw children who could not speak and would never be able to live independently. He also discovered chatty people who would become professors in the various sciences and would talk at length about their special passions for numbers or chemistry.

Asperger, therefore, did not just discover what would be known as the high functioning end of the spectrum – Asperger’s Syndrome. He discovered the entire spectrum amidst an unusual situation. Asperger’s lab was a sort of combination child psychology clinic and school. The clinic was set up to function as a humane version of society in which the children would learn to relate to each other while being treated with respect by the clinicians who were constantly observing them. Many of the teaching methods employed at the clinic were developed in collaboration with the children.

Targeting Children: Erwin Jekelius and Hans Asperger in Nazi-Controlled Austria

In 1938, everything changed at Asperger’s clinic when Nazi Germany invaded Austria as part of the Third Reich’s political maneuverings which led to the onset of World War II. Many of Asperger’s associates fled, some committed suicide, but Asperger attempted to continue his work.

The children in Asperger’s care immediately became targets of the Nazi eugenic programs. One of Asperger’s former colleagues became the leader of a secret extermination program against disabled children that became the dry run for the Holocaust. Children with hereditary conditions – i.e. Autism (though unnamed in 1938), Epilepsy, Schizophrenia, inherited blindness – were at risk. Almost immediately, Asperger created ways to protect the children in his clinic.

Irwin Jekelius, an Asperger colleague in Vienna, rose through the ranks of the Nazi Party and became the director of what had been a rehab facility for alcoholics. Under his leadership, it became a center for collecting and euthanizing disabled children. Under the adult and child euthanasia programs, more than 200,000 children and adults were murdered. Jekelius himself oversaw 789 children murdered in the Am Spiegelgrund Children’s Clinic in Vienna, most of whom had what today would be called Autism but was in those days called feeble-minded.

The Nazi ideas for eugenics and sterilization were not new and were not patented Third Reich ideologies. They were imported from the United States, whose National Academy of the Sciences had hosted the 1921 Second International Congress on Eugenics in New York City. The NAS had openly promoted both eugenics and sterilization in journals such as Science.

One way Asperger would attempt to protect the children and his work was to present to the Nazis, in the first public talk on Autism in history, his most promising cases. It is from that speech and in that attempt to save lives that the idea of high functioning versus low functioning autism derived.

On October 3, 1938, Asperger attempted to emphasize the children’s “whole harmonious personalities.” He tried to show that the children’s’ gifts were inextricable from the challenges that they faced in life due to their Autism. He argued that these children could develop in ways that no one can predict as long as they were given the adequate forms of support and education that he had been developing in his clinic. He even suggested at a later date that Autistic children could be talented code breakers for the Third Reich.

The speech by Asperger challenged the ideology of the Third Reich even more directly. “Not everything that steps out of line, and is ‘abnormal,’ must necessarily be inferior,” Asperger told the crowd of Nazi supporters. It was a dangerous thing to say at a dangerous time. The Gestapo, the Nazi secret police force, came to his clinic three times to arrest Asperger and ship the children to concentration camps or to Kinderfachabteilungen, “specialist children’s wards” for what was called “final medical treatment.” Asperger’s supervisor, though a Nazi loyalist, had developed an affection for Asperger and believed he was doing good work. He saved Asperger’s life, and Asperger survived the war.

After the Fall: The End of Asperger’s Clinic the Rise of Propaganda

Asperger was drafted by the Nazis and later went off to the war in Croatia for a short time. He continued to keep in touch with those in his clinic, a clinic that was not long for life. The Allies eventually bombed the clinic into the ground as the University of Vienna was targeted as the leading intellectual center for what the Germans called “racial hygiene.” The center in which Asperger had worked and advanced the cause of children who functioned differently had been turned into a collection of Germans and Austrians determined to “purify” differences from heredity rather than appreciating them.

The German government was constantly pumping out streams of propaganda that framed disabled people in general as burdens on society. They had pictures of “normal” German citizens with disabled people sitting on their shoulders. “Two-hundred Reichmarks a week!” the propaganda would say, alluding to the cost of caring for a disabled person in German society. Similar to the modern debates over capital punishment, the Nazi argument was one that argued that the value of cost was superior to lives with no worth. It was a matter of medical efficiency that disabled people had to be flushed from the German-controlled gene pool.

Was Asperger a Nazi Sympathizer Responsible for the Deaths of Children?

Whether or not Asperger was a Nazi sympathizer is still a hotly debated issue, historically. Steve Silberman, author of Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and How to Think Smarter about People who Think Differently”, argues vehemently that Asperger is quite the opposite of a Nazi sympathizer and that he saved many children from almost certain extinction.

In John Donovan and Caren Zucker’s book, In a Different Key, lecturer Herwig Czech (Medical University of Vienna) provides evidence that Asperger participated in sending children to the Am Spiegelgrund Clinic, a clinic that was most certainly known by that time as a killing ward for children.

While the argument over Asperger’s political leanings and actions taken as potential self-preservation continues, what is not debated is his influence on the research. He changed the lives of millions who have since been diagnosed with Autism by providing both grounds for diagnosis and an opinion that differences should be advantages and not disadvantages.

The Faces and Minds of Autism

People with autism often have trouble making sense of social signals in real time – parsing facial expressions, interpreting body language, and interpreting tone of voice. They may come across as disconnected from the people around them. However, they may be listening very intensely even if they appear not to be paying attention. They generally have difficulty making sense of the social signals that non-autistic people use to keep each other comfortable, things that one does to cause people to like or dislike them. Some autistic people may have difficulty with irony or sarcasm, things that are not literal.

Autistic people may do things repetitively. There is a very typical behavior called stemming, or self –stimulation, such as the flapping of the hands or fidgeting with an object. Autistic people stem to regulate their own energy or their own anxieties. It is a very soothing coping mechanism to people with autism. In the past, psychiatrists viewed stemming as a negative behavior and often suggested punishment. Today, it is seen as a relatively harmless response, just as fidgeting is harmless to non-autistic people.

Note: Midnight Writer News will continue the Asperger story with a discussion of Leo Kanner who, until Asperger’s research was popularized and accepted publicly in the 1970s and 1980s, formulated the previously accepted model of autism. We will also delve further into the accusations of sympathy for the Third Reich.