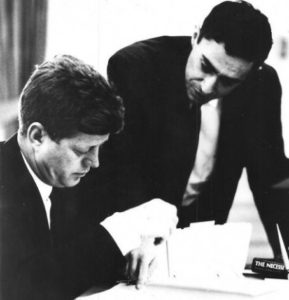

Richard Goodwin was part of a group of young, idealistic, Northeastern liberals who entered the oval office with President John F. Kennedy in 1961. At 31, Goodwin had joined the administration as Ted Sorensen’s speechwriting assistant before being appointed to the role of JFK’s point man on Latin American affairs.

Goodwin had come to Washington D.C. just out of college in the 1950’s to work as a congressional investigator during the television quiz show scandals. Like Kennedy, Goodwin had come from an affluent Massachusetts family. Also like Kennedy, Goodwin believed in the power of the Latin American people more than the oppressive oligarchies that had dominated the region throughout the 1950’s.

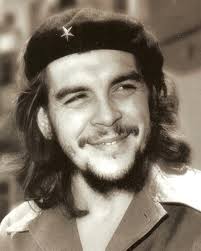

The Rise of Ernesto “Che” Guevara

Che Guevara was an Argentine. More importantly, Che Guevara was a revolutionary. Guevara had left a privileged life in Buenos Aires to become a physician for the poor. He traveled throughout Latin America immersing himself in the lifestyle of the people for which he would fight. He chronicled these travels in a work he called The Motorcycle Diaries.

Che’s first direct contact with America’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) came in defense of the democratically-elected Guatemalan government of Jacobo Arbenz in 1951. This fight inspired Che to dedicate his life to armed revolution. If the oppressive governments were armed, why should the revolution not be?

Guevara joined Fidel and Raul Castro’s Cuban uprising after meeting them both in Mexico in 1956. Che shared the black beret, olive fatigues, and combat boots that would become a symbol of Castro’s 26th of July Movement for decades. Castro’s victory over the Fulgencio Batista regime led to Che’s appointment as Cuba’s economic minister.

The Kennedy Men vs. The Military-Industrial Complex

The 1961 Bay of Pigs disaster led to Kennedy’s distrust of the national security establishment that he believed had lied to him. It was this same “military-industrial complex” that outgoing President Dwight D. Eisenhower had warned the nation about in his farewell address. Now it would be Kennedy, a Democrat, whose struggle with the same military-industrial complex would later possibly cost him his life.

As Kennedy wanted a serious change in American policy in Latin America, more and more decisions were placed into the hands of Kennedy men rather than Washington men.

“We can’t embrace every tin horn dictator who tells us he’s anticommunist while he’s sitting on the necks of his own people,” Kennedy once told Goodwin. “And the United States government is not the representative of private business. Do you know in Chile the American copper companies control over 80% of all the foreign exchange? We wouldn’t stand for that here. And there’s no reason they should stand for it. All those people want is a chance for a decent life, and we’ve let them think that we’re on the side of those who are holding them down. There’s a revolution going on down there, and I want to be on the right side of it. Hell, we are on the right side of it. But we have to let them know it, that things have changed.”

Goodwin, Che, and the Alliance for Progress

Goodwin embodied that desire for change when he traveled to Montevideo, Uruguay for an Alliance for Progress conference in August 1961. The Alliance for Progress was Kennedy’s attempt at reaching out a hand to Latin American countries that had become distrustful of America during previous administrations. The multi-billion dollar aid package would assist in the building of schools, hospitals, and housing, while also encouraging economic and agrarian reform.

Guevara was the only attendee of the conference to give the Alliance for Progress a cool reception. He noted that there would be no Alliance without the Cuban Revolution since the United States had seemed largely uninterested in Latin American poverty until they (Che, Fidel, and Raul) had marched into Havana. He expressed skepticism that any privileged class would make a revolution against its own class.

Guevara accused the U.S. of planning another covert assault on Cuba at Guantanamo Bay as a pretext for war. He was right. That was a plan floated around the military-industrial complex after the Bay of Pigs fallout. Kennedy had rejected it outright. The main idea of Che’s speech was his long held belief that true change would only come through an armed rebellion of the downtrodden.

Despite his opposition, it was Guevara who first reached out his hand to Goodwin to form an alliance of his own. Che sent Goodwin a polished mahogany box filled with fine Cuban cigars. A note was attached: “Since to write to an enemy is difficult, I limit myself to extending my hand.” It was an incredible gesture from a revolutionary to a representative of a country that had openly sponsored a failed dissident invasion at the Bay of Pigs just four months earlier. It also broke almost every rule of formal diplomatic relations. After Che’s fiery speech, however, Treasury Secretary Douglas Dillon, the leading U.S. representative at Montevideo, forbade any informal discussion between Goodwin and Guevara. Che, however, was undeterred.

Goodwin and Che: Meeting in Montevideo

Goodwin, without Dillon, attended a diplomat’s birthday party on the final night of the conference. Guevara showed up at the party solely to corner Goodwin into an informal chat. Goodwin needed neither convincing nor cornering. The chat evolved into an all-night conversation. After being introduced, Che sat on the floor to talk. Goodwin, not intimidated and not pretentious, was not afraid to literally and symbolically join Che at his level. He, too, sat on the floor. Brazilian and Argentine officials, realizing the importance of the moment, encouraged them both to take seats.

Che humorously opened the conversation by thanking Goodwin for the Bay of Pigs disaster. By the United States casting itself as the invaders, Castro’s regime within Cuba was consolidated as Cubans patriotically rallied around their new bearded leaders. Both sides realistically knew that the political climates within both nations would not allow for any type of mutual partnership or alliance, but a state of coexistence seemed possible.

Che informed Goodwin that the Cuban government would address two issues very important to Kennedy. Cuba would agree not to engage in any political or military alliance with Moscow (thus not becoming a satellite nation of the Soviet Union), and Castro would be willing to reconsider the island nation’s policy of aiding revolutions in other Latin American countries. The Kennedy administration had stated that it would not tolerate Cuba’s policy of “exporting revolution.” Apparently, the only revolutions the executive branch would continue to support would be those controlled and coerced by the CIA in third world countries with attractive raw materials and vulnerable markets.

Cuba, in return, expected two items from the United States. First, the U.S. would have to promise not to support a forceful overthrow of the Cuban (Castro) government. Rumors of the potential Guantanamo Bay invasion were rampant throughout the hemisphere. Second, yet equally important to the Castro administration, the Kennedy administration would have to move toward lifting the trade embargo that had been imposed on Cuba by the United States.

Goodwin and Guevara parted ways at 6 a.m., promising to share details of their discussion first with Kennedy and Castro directly. Both had exhibited a penchant for freelance diplomacy that night in Uruguay, but neither knew exactly what kind of reaction they would face in their respective countries.

And meanwhile, back in Washington D.C. and Havana…

Goodwin and Kennedy shared Che’s gift of Cuban cigars as Goodwin recalled the entire conversation to the president. Che felt the same optimism as he informed Fidel. Kennedy, showing what in hindsight was a startling bit of political naiveté, asked Goodwin to write a memo of the conversation with Che to Robert McNamara, Dean Rusk, McGeorge Bundy, and the rest of the national security / foreign policy high command.

Kennedy may have expected a typical reaction from the hawkish GOP when the story eventually leaked, but he probably underestimated the venom that came from his own cadre of Truman and Eisenhower Cold Warriors. Senator Barry Goldwater (R-AZ) called on Kennedy to rid the White House of liberals like Goodwin. Where Goodwin was calling for a silence on Cuba that could have led to an agreement, the foreign policy team was bellowing for a continuance of the hard line against Castro.

Not a Pax Americana

In the end, Goldwater and the military-industrial complex got what they had wanted. JFK demoted Goodwin in November 1961. The establishment won this small battle with Kennedy, but the new president was determined to maintain control of his own foreign policy initiatives. He had made permanent enemies of the CIA and its group of sacred cows over the fallout from the Bay of Pigs. Kennedy had threatened to “splinter the CIA into a thousand pieces and scatter it into the winds.” The demotion of Goodwin and the other young liberals ended up being a decision without consequence for Kennedy. The results were the same with Goodwin out as they would have been with him in – the level of dislike and distrust between Kennedy and the military-industrial complex grew daily.

Goodwin later married historian Doris Kearns (Goodwin) and became a regular contributor to documentaries and books on the Kennedy years. The possibility of peaceful relations between the United States and Cuba ended when Kennedy was gunned down by a high-level group of conspirators in Dallas on November 22, 1963. Guevara had a falling out with Castro and would later be assassinated fighting for revolution in the jungles of Bolivia in 1967. The deaths of both Kennedy and Guevara are rumored to have some high level of CIA involvement.

There would be no official peace between the United States and Cuba for nearly fifty years. Much to the disgust of Guevara, Castro signed an alliance with the Soviet Union in 1963. Castro would become the leading exporter of revolution in Latin America throughout the latter half of the 20th century. The United States continued to support potential rebellions to oust Castro, including CIA plots to take his life. The trade embargo and the ban on movement between the two countries has lessened in recent years, yet the Castro regime still officially stands with Raul at its head. Fidel died in 2016. The secret peace agreed to by Guevara and Goodwin – sealed with the moral certitude of a handshake and authentic Cuban cigars – was lost in the bureaucratic posturing of Cold War politics.