by S.T. Patrick

Bob Woodward’s newest book, Fear: Trump in the White House, stands atop the New York Times Bestseller list for Hardcover Non-Fiction. Woodward skeptics and Watergate revisionists still question Woodward’s monarchical hold on modern journalism and publishing. In this issue, contributing editor S.T. Patrick continues a series that will spotlight the questionable tactics and little-known fallacies of Bob Woodward’s journalistic career. This is part two in the series.

* * * * *

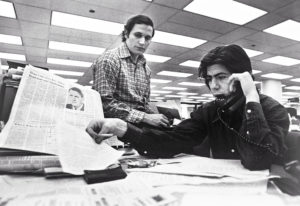

On March 6, 1989, would-be authors Len Colodny and Robert Gettlin sat with The Washington Post’s Bob Woodward in preparation for what would be their upcoming book Silent Coup: The Removal of a President (1991). Woodward and co-author Carl Bernstein had written what establishment historians and educators considered the two books of record on the end of Richard Nixon’s presidency: All the President’s Men (1974) and The Final Days (1976). Both would be made into films. On this day, however, Colodny and Gettlin had confirmed information that would turn the Watergate story – and Woodward’s role in it – on its head.

Woodward verified that he had worked at the Pentagon as a communications officer. This was already in contrast with the book and film notion of Woodward as a bottom-rung hoofer who was fighting his way up the journalistic ladder at The Post. The film created the legend that all Woodward had done was to write about the lack of cleanliness in local restaurants. When the editors debated the oncoming storm of Watergate reporting, it was in an effort to decide if Woodward was even qualified to write such a consequential story. In reality, he was, and the editors knew it.

Woodward denied to Gettlin that he had any other function at the Pentagon beyond once being a communications watch officer. Gettlin then asked if Woodward had ever done “any briefings of people”?

“Never! … And I defy you to produce somebody who says I did a briefing. It’s just… it’s not true,” Woodward responded.

The conversation turned to Gen. Alexander Haig, who had become Nixon’s chief of staff upon the urged resignation of H.R. Haldeman. Tim Weiner, upon Haig’s death in 2010, wrote in The New York Times that Haig had been the “acting president” while Nixon was pre-occupied with Watergate. Haig biographer Roger Morris wrote that President Gerald Ford’s pardon of Nixon was also a de facto pardon of Haig, as well. Haig had played an important role in the transition from Nixon to Ford, and had even been one of the most instrumental voices privately encouraging Nixon’s resignation. If Haig had a previous working relationship with Woodward, and if Woodward’s stories were contradictory to the Nixon administration’s best interests, then the relationship and roles of both Woodward and Haig in relation to Nixon’s fall demanded examination.

“I never met or talked to Haig until some time in the spring of ’73,” Woodward responded. That Woodward had never done briefings, had never been a briefing officer, and had never met Haig until 1973 were ideas that sources “in a position to know,” as Gettlin called them in the interview, contradicted.

Lest someone assume that Colodny and Gettlin’s sources on Woodward were journalistic rivals or disenfranchised victims made unemployable by Watergate’s political aftermath, they were not. And unlike Woodward’s most notable sources, they were not kept hidden under “deep background.” Colodny and Gettlin’s confirmation came from Adm. Thomas H. Moorer, Melvin Laird, and Jerry Friedheim, all of who can be read and heard on “Watergate.com.”

Adm. Moorer, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (1970-1974), told Gettlin that he was aware that Haig was being briefed by Woodward. Moorer was in close contact, sometimes “on the telephone with Haig eight or nine times a day.”

Laird, Nixon’s secretary of defense, said, “I was aware that Haig was being briefed by Woodward… He was there on a temporary assignment.” This was while Woodward was working in communications at the Pentagon.

Friedheim, a Pentagon spokesperson, elaborated on Woodward’s Pentagon associations in the pre-Watergate era. “He was definitely there, and he was moving in circles with– You know, e– As a junior officer, as a briefer, but obviously it’s somebody that they thought was sharp enough to do those things,” Friedheim said. “He was moving with those guys, Moorer, Haig, the NSC staff, and other military types.”

Colodny and Gettlin were not the first, nor were they the last, to tie Haig to the role of Woodward’s most famous Watergate source, “Deep Throat.” In his 1984 book Secret Agenda: Watergate, Deep Throat, and the CIA, Jim Hougan wrote that Haig was the “’prominent official’ within the Nixon administration who most closely fits Woodward’s description of his source.” There are Watergate historians who still believe that Deep Throat was a composite of sources, with Haig being chief among them, or someone other than the FBI’s Mark Felt.

The release of Secret Agenda was a new starting point for Watergate skeptics in 1984; Silent Coup reorganized them once again in 1991. Author Ray Locker will continue to question Woodward’s links to the Nixon White House in 2019’s Haig’s Coup.

Woodward, exasperated by the questioning of Colodny and Gettlin further in the 1989 interview, referenced the briefing revelation and the Haig tie as a “totally erroneous story… that I briefed somebody in the Pentagon… and that there’s this coup going on.” He had yet to learn that no less than Moorer, Laird, and Friedman had all openly established a Woodward link to Haig.

He would also repeatedly ask about the nature of the interviewer’s sources, about whom Colodny and Gettlin then vaguely referred. It seems that Woodward was perturbed to be the target of yet-unnamed sources who verified information and scenes in which he was involved. He had popularized the practice and allowed the subjects to deal with the consequences. But Hougan, Colodny, Gettlin, and Locker have since put that translucent lens back on Woodward.

As the Reagan era dawned, Woodward would turn to the entertainment industry for his first solo work, a biography of John Belushi, but once again, not without controversy. The Eighties would also bring one of the most bizarre, “Veiled” moments of Woodward’s notable career.