Radical Islamic terrorists, American citizens captured and held for ransom, Marines on special missions, and, of course, Benghazi. These are all significant events and controversies of the present day. These modern issues have served to spur the United States into multiple wars, spend 70 billion dollars, and bury 6,852 American soldiers. But there is a little known US war that dealt with these same issues, and it occurred during America’s infancy as a nation.

Radical Islamic terrorists, American citizens captured and held for ransom, Marines on special missions, and, of course, Benghazi. These are all significant events and controversies of the present day. These modern issues have served to spur the United States into multiple wars, spend 70 billion dollars, and bury 6,852 American soldiers. But there is a little known US war that dealt with these same issues, and it occurred during America’s infancy as a nation.

The Barbary Coast

In 1785, before the United States had even elected its first president, two American merchant ships sailing off the North African coast were boarded by Algerian pirates. The Dauphin and the Maria, were hopelessly outgunned by the pirates’ ships. The goods on the vessels were claimed in the name of the Algerian ruler. The crews were delivered to Algiers and forced into slavery. The captain of the Dauphin, Richard O’Brien, would be a slave for 10 years before regaining his freedom. Most of the sailors were forced into hard labor and could only wait for their government to negotiate their release.

These American merchant ships had traveled along the dangerous Barbary Coast, which included Morocco, Algiers (Algeria), Tunis (Tunisia) and Tripoli (Libya). These countries did not only target American ships. Several European nations also paid large tributes to the Barbary rulers to avoid being attacked, enslaved, and ransomed. Unfortunately, the United States had a distinct disadvantage in this regard. As a young nation, the prevailing belief was that the U.S. government could scarcely afford tribute since they lacked a robust treasury and the strength of a navy to militarily dissuade the Barbary pirates.

Diplomacy First

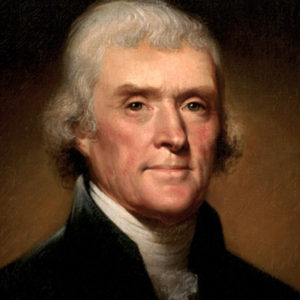

At this time, Thomas Jefferson was the American minister to France, and his good friend, John Adams, was ambassador to Great Britain. Adams and Jefferson met to discuss how to deal with the piratical Barbary States. Adams believed there had to be a diplomatic solution in dealing with the North Africans. In fact, the American government had initially approved payment to these nations to ensure safe travel for their merchant ships, but delivery of the money had been slow. Since the US had many debts from the Revolutionary War, it became clear that the best way to increase revenue was through increased commerce and trade. Therefore, the only path to a thriving economy was to find a solution to the Barbary pirate problem.

Adams and Jefferson discussed a diplomatic solution with the Tripolitan ambassador to Britain. When Adams questioned the justification of attacking the vessels of a peaceful country, the Muslim diplomat referenced the Qur’an. He explained that if a nation had not acknowledged the prophet Mohammed, then they were infidels and it was their right to plunder and enslave those sinners. Despite the setbacks in the negotiations, Adams remained hopeful and wanted to continue his attempt to strike a bargain. Jefferson, however, began to believe that there was no other recourse but war. The only problem was that the United States lacked a navy.

Adams and Jefferson discussed a diplomatic solution with the Tripolitan ambassador to Britain. When Adams questioned the justification of attacking the vessels of a peaceful country, the Muslim diplomat referenced the Qur’an. He explained that if a nation had not acknowledged the prophet Mohammed, then they were infidels and it was their right to plunder and enslave those sinners. Despite the setbacks in the negotiations, Adams remained hopeful and wanted to continue his attempt to strike a bargain. Jefferson, however, began to believe that there was no other recourse but war. The only problem was that the United States lacked a navy.

Jefferson strongly disliked the idea of using a “purchased peace” with the Barbary States. By 1789, Jefferson had returned to the US and discovered that he had been appointed to the position of Secretary of State by President Washington (Adams was vice-president). Although he believed a navy could eliminate the North Africa’s commerce and end their piracy, he stopped short of calling for direct military action. As someone who understood the Constitution that members of his cabinet had framed, Jefferson clearly knew that only Congress could decide whether the US entered a war.

President Washington was a fierce supporter of neutrality in international affairs. Washington endorsed the Neutrality Proclamation of 1793, which declared that the U.S. would remain neutral in providing aid to either side of warring nations. Jefferson was so against this legislation that he stepped down from his post as Secretary of State. It was during this time that Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, the “Father of the Constitution,” began an exchange of pamphlets outlining their opinions on the matters of neutrality, war and the federal government. According to Hamilton, Congress had the sole right to declare war, but it was the duty of the President to preserve the peace. While Madison disagreed with the Neutrality Proclamation, he did believe that creating a navy would excessively increase the size of the federal government. Despite Washington and Hamilton’s reservations, Congress would pass the Act to Provide a Naval Armament. This act authorized the purchase of six frigates to begin the nation’s navy. Over the next eight years, while these new naval ships were being built, the U.S. continued to send tribute to the Barbary nations.

War Begins

In March of 1801, Thomas Jefferson became the new President of the United States by defeating John Adams. Later that same year, the Bashaw Yusuf of Tripoli declared war and demanded additional tribute in response to late payments by the U.S. In response, Jefferson refused to give any further tribute and sent the naval fleet to ensure safe passage for merchant vessels. President Jefferson ordered the fleet to create blockades and bombard harbor cities. Jefferson still had reservations about whether or not he was truly authorized to use military force without Congress declaring war.

Jefferson brought the question to his cabinet. Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin felt that “the executive can not put us in a state of war”, but if another country attacked us, “the command and direction of the public force then belongs to the Executive.” The Attorney General Levi Lincoln believed, “Our men of war may repel an attack, but after the repulse, may not proceed to destroy the enemy’s vessels.”

Over the next several years, the United States won minor skirmishes and suffered humiliating defeats. The USS Enterprise won its first battle against the Tripoli and at the same time the USS Philadelphia trapped an important Tripolitan vessel at Gibraltar. Jefferson and the American public celebrated these wins and, like any victory, they made the President’s decision to go to war seem valid. With the continued support of Congress, President Jefferson signed into law the “Act for the Protection of the Commerce and Seamen of the United States, Against Tripolitan Corsairs”. The other Barbary nations of Tunis, Algeria and Morocco had not declared war against the United States at this time. Jefferson now had the power to attack Tripolitan ships first and send as many ships as he deemed necessary to protect the nation’s merchant ships and commerce.

Unfortunately, the public elation was short lived. The blockade of the Tripoli produced little results and the crew and captain of the trapped enemy ship escaped into Gibraltar and made their way home. The new commander of the American fleet, Captain Morris, brought his family aboard and was far more interested in socializing with the elite of Gibraltar than protecting America’s interests. Three more ships evaded the American blockade of Tripoli and proceeded to capture another U.S. merchant vessel and enslave the crew. Morris would be court-martialed upon returning home and dishonorably discharged from the Navy.

In 1803, Morocco and Algiers declared war on the United States. Only Tunis maintained a marginal peace with America. Congress authorized Jefferson to add more warships to the naval force. There were now nine naval vessels anchored off the coasts of the Barbary nations. They made such an impressive show of force off the coast of Morocco that the sultan was most apologetic and immediately agreed to a peace without any further mention of tribute being paid.

Despite the victorious showdown with Morocco, the naval fleet would soon face a disastrous defeat with Tripoli. While the USS Philadelphia was charged with blockading the Tripoli coast, it sighted a ship trying to slip past the blockade and pursued it. The enemy vessel was faster, more maneuverable and outran the larger Philadelphia. As the American vessel was admitting defeat and turning away from the coast, it ran aground. The crew was unable to dislodge the ship, despite throwing the cannons overboard in order to lighten the load. The Tripolitan soldiers saw that the Philadelphia was in trouble and were soon headed towards the ship with the intent to capture the vessel and its crew. The captain of the Philadelphia, Captain William Bainbridge, ordered all guns and ammunition thrown overboard and he destroyed all pertinent papers with American intelligence. He then gave the order to surrender. The Philadelphia was occupied and the crew enslaved. Instead of allowing the ship to be used against its own country’s navy, a plan was hatched to destroy it. A small American vessel, the Intrepid, and its captain, Stephen Decatur, Jr., were tasked with boarding the Philadelphia under the cover of darkness to set it ablaze. The mission was successful. The Philadelphia had been destroyed and was no longer a symbol of Tripoli’s victory over the American navy.

Military Coup

In addition to using the new American navy to intimidate the Barbary powers, President Jefferson, Secretary Madison and Consul William Eaton had developed an ancillary plan to gain control of Tripoli. This new strategy involved overthrowing Bashaw Yusuf and supporting his brother, Hamet, in regaining the throne. Eaton, the American consul to Tunis, traveled to Egypt to find Hamet and set in motion the plan to overthrow the Tripolitan government. Eaton was accompanied by two Navy midshipmen and eight US Marines. Once Hamet was located, he and Eaton signed a mutually beneficial treaty in which the United States would supply troops and supplies in order to place Hamet on the throne. He, in turn, would release all American prisoners and hand over the men accused of targeting the U.S. ships. The plan to overthrow Bashaw Yusuf depended on being able to hire mercenaries, and the hope that the Tripolitan citizens would flock to Hamet’s side and support him in his quest to regain the throne. The military force was to march 500 miles across the desert to the city of Derne and capture it. The soldiers would then continue to Benghazi and occupy it, at which point American warships would convoy them to the capital of Tripoli to complete their military and political coup.

During the battle for Derne, three American ships began firing into the town while the ground forces charged the city wall. Two of the U.S. Marines were killed, but the Tripolitan soldiers quickly abandoned the city. This was a decisive victory for the combined forces of Hamet’s mercenaries and the Americans. Despite the momentum the victory created, there came an unexpected halt to any further aggressions against the Tripolitans. Tobias Lear, the US Consul General to the Barbary States, sent a message to Eaton ordering him not continue into Benghazi and cede the ground gained. Lear was in diplomatic talks with Bashaw Yusuf and a peace agreement was imminent. The Americans were forced to abandon Hamet and his allies and quickly leave Derne. The peace agreement was signed and the essential goals had been achieved. American merchant ships could now sail without fear and all prisoners were released.

Lasting Effects

The Barbary War, although not widely known, created significant precedents that were likely not intended. The war marked the creation of the United State Navy and saw the first American flag planted in another sovereign nation in victory. It was also during this crisis that the executive branch began to believe that they had the power to send the military into battles without the congressional approval. Additionally, this was the first instance of American interference in another country’s government to suit America’s needs and place into power someone friendly to U.S. interests.

The U.S. Constitution was written to outline the powers given to the three branches of the federal government. It sought to control the government from having an excessive amount of centralized power. The founders wrote the document in such a way as to create flexibility for future governments to operate and while it did produce some uncertainty, it was really the first three presidential administrations that created lasting and powerful precedents.

Jefferson’s secret mission to overthrow Tripoli’s reigning government was surely an overreach of presidential authority. Once the covert operation had been revealed to Congress after the fact, there was indeed discontent. This congressional dismay wasn’t due to excessive executive power; rather, many congressmen were dismayed that the political coup was not seen to completion.

There are many instances throughout American history when presidents took the authority upon themselves to send military forces into battle without Congressional approval. Americans may question the motives for such actions, but they no longer debate whether a president can legally and constitutionally send our soldiers on missions.